Yang Family Tai Chi School Promotes Tai Chi Practice for Brain Health

The lower dantian in Taijiquan: | |

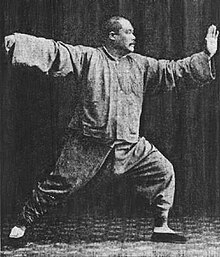

Yang Chengfu (c. 1931) in Single Whip posture of Yang-style t'ai chi ch'uan solo form | |

| As well known as | Tàijí; T'ai chi |

|---|---|

| Focus | Chinese Taoist |

| Hardness |

|

| Country of origin | Greater Mainland china |

| Creator | Chen Wangting or Zhang Sanfeng |

| Famous practitioners |

|

| Olympic sport | Sit-in simply |

| Tai chi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 太極拳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极拳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Taiji Boxing" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tai chi (simplified Chinese: 太极; traditional Chinese: 太極; pinyin: Tàijí ), short for T'ai chi ch'üan or Tàijíquán (太極拳), sometimes likewise known as "Shadowboxing",[i] [2] [3] is an internal Chinese martial art skilful for defense training, health benefits, and meditation. Tai chi has practitioners worldwide.

Yang Shaohou, Yang Chengfu, Wu Chien-ch'üan and Sun Lutang promoted the art for its health benefits beginning in the early 20th century.[4] Its global following may be attributed to overall benefit to personal health.[v]

Many forms are skilful, both traditional and modern. Most modern styles trace their development to the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu (Hao), Wu, and Sun. All trace their historical origins to Chen Village.

Yin and yang [edit]

The concept of the taiji ("Supreme Ultimate"), in contrast with wuji ("without ultimate"), appears in both Taoist and Confucian philosophy, where it represents the fusion or mother[half dozen] of yin and yang into a unmarried ultimate, represented past the taijitu symbol ![]() . Tai chi theory and practise evolved in agreement with Chinese philosophical principles, including those of Taoism and Confucianism. Zou Yan (鄒衍; 305 BC – 240 BC) was a Chinese philosopher best known every bit the representative thinker of the Yin and Yang Schoolhouse (or School of Naturalists) during the Hundred Schools of Idea era in Chinese philosophy.

. Tai chi theory and practise evolved in agreement with Chinese philosophical principles, including those of Taoism and Confucianism. Zou Yan (鄒衍; 305 BC – 240 BC) was a Chinese philosopher best known every bit the representative thinker of the Yin and Yang Schoolhouse (or School of Naturalists) during the Hundred Schools of Idea era in Chinese philosophy.

Taijiquan is a complete martial fine art system with a full range of bare-paw movement ready and weapon forms as in the Taiji sword and Taiji spear based on the dynamic relationship betwixt Yin and Yang.

While tai chi is typified past its ho-hum movements, many styles (including the three most popular: Yang, Wu and Chen) have secondary, faster-paced forms. Some traditional schools teach partner exercises known as tuishou ("pushing hands"), and martial applications of the postures of dissimilar forms (taolu).

Internal vs external [edit]

In Prc, tai chi is categorized nether the Wudang grouping of Chinese martial arts[vii]—that is, arts applied with internal power.[eight] Although the term Wudang suggests these arts originated in the Wudang Mountains, it is used simply to distinguish the skills, theories and applications of neijia (internal arts) from those of the Shaolin grouping, or waijia (hard or external) styles.[9]

Some martial arts require students to wear a uniform during practice. In general, tai chi does non specify a uniform, although teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.[10] [11]

Due to the historical context in which tai chi was introduced to the Manchu imperial prince, the cultivation and practice of tai chi have been enumerated by the literati court ministers and even a verse form written by one of the Manchu princes' private tutors praising the founder of Yang family tai chi. And in the "T'ai-chi classics", writings by tai chi masters. The physiological and kinesiological the body's movement are characterized past the round motion and rotation of the pelvis based on the metaphors of the pelvis equally the hub and the arms and feet are alike to the spoke of a wheel. Furthermore, the respiration of jiff are coordinated with the physical movements in a state of deep relaxation, rather than muscular tension, in society to guide the practitioners' to a state of homeostasis.

Practice [edit]

- Meditation: The focus and calm cultivated by the meditative aspect of tai chi is seen equally necessary for maintaining wellness (in the sense of relieving stress and maintaining homeostasis) and in the application of the form as a soft style martial art.

- Movement: Tai chi is the practice of advisable change in response to outside forces, of yielding to and engaging an attack rather than meeting it with opposing strength.[12] Physical fitness is an important stride towards effective self-defense.

- Traditional Chinese medicine is taught to advanced students in some traditional schools.[13]

Tai chi training involves five elements:

- taolu (solo hand and weapons routines/forms)

- neigong and qigong (breathing, motility and awareness exercises and meditation)

- tuishou (Push Easily drills)

- sanshou (Striking techniques).

Etymology [edit]

Tai Chi was known equally "大恒" during the Warring States period. The silk version of I Ching recorded this original name. Due to the proper name taboo of Emperor Wen of Western Han Empire , "大恒" changed to "太極.". Sundial shadow length changes represent traditional Chinese Medicine with 4 elements theory instead of Confucian politician-based five elements theory.[14] In the showtime, the color white was associated with Yin, while black was associated with Yang. Confucianism uses the reverse.

The term taiji is a Chinese cosmological concept for the flux of yin and yang. 'Quan' means technique.

Tàijíquán and T'ai-chi ch'üan are two different transcriptions of three Chinese characters that are the written Chinese proper noun for the artform:

| Characters | Wade–Giles | Pinyin | Pregnant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 太極 | t'ai chi | tàijí | the relationship of Yin and Yang |

| 拳 | ch'üan | quán | technique |

The English language language offers two spellings, one derived from Wade–Giles and the other from the Pinyin transcription. Most Westerners often shorten this name to t'ai chi (often omitting the aspirate sign—thus becoming "tai chi"). This shortened proper noun is the same equally that of the t'ai-chi philosophy. Yet, the Pinyin romanization is taiji. The chi in the name of the martial art is non the aforementioned equally ch'i (qi 气 the "life force"). Ch'i is involved in the practice of t'ai-chi ch'üan. Although the word 极 is traditionally written chi in English, the closest pronunciation, using English language sounds, to that of Standard Chinese would be jee, with j pronounced as in leap and ee pronounced as in bee. Other words exist with pronunciations in which the ch is pronounced as in gnaw. Thus, it is of import to utilise the j sound. This potential for defoliation suggests preferring the pinyin spelling, taiji. Nearly Chinese utilise the Pinyin version.[fifteen]

History [edit]

Tai chi'due south formative influences came from Taoist and Buddhist monasteries, every bit recounted in legend. Nonetheless, some schools claim that tai chi sprang from the theories of Song dynasty Neo-Confucianism (synthesis of Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian traditions, especially the teachings of Mencius).[9] These schools believe that tai chi theory and practice were formulated by Taoist monk Zhang Sanfeng in the 12th century, at about the same time that the principles of the Neo-Confucian school were ascent.[nine]

Nevertheless, modern research doubts those claims, pointing out that a 17th-century slice called Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan (1669), composed by Huang Zongxi (1610–1695), is the earliest reference indicating a connectedness betwixt Zhang Sanfeng and martial arts. Claims of connections between tai chi and Zhang Sanfeng appeared no earlier than the 19th century.[16]

Yang Luchan trained with the Chen family unit for eighteen years before he started to teach in Beijing, which strongly suggests that his work was heavily influenced by, the Chen family art. The Chen family unit trace their art back to Chen Wangting in the 17th century. Martial arts historian Xu Zhen claimed that the tai chi of Chen Village was influenced by the Taizu changquan style practiced at nearby Shaolin Monastery, while Tang Hao idea it was derived from a treatise by Ming dynasty general Qi Jiguang, Jixiao Xinshu ("New Treatise on Armed forces Efficiency"), which discussed several martial arts styles including Taizu changquan.[17] [xviii]

What is now known equally tai chi appears to have received this appellation effectually the mid-19th century.[16] Imperial Court scholar Ong Tong witnessed a demonstration by Yang Luchan earlier Yang had established his reputation as a teacher. Afterwards Ong wrote: "Hands holding Tai chi shakes the whole world, a breast containing ultimate skill defeats a gathering of heroes." Earlier this time the fine art may have had other names, and appears to have been generically described by outsiders every bit zhan quan ( 沾拳 , "touch on battle"), Mian Quan ("soft boxing") or shisan shi ( 十三式 , "the 13 techniques").[xix]

Standardization [edit]

In 1956 the Chinese government sponsored the Chinese Sports Commission (CSC), which brought together four wushu teachers to truncate the Yang family hand form to 24 postures. This was an attempt to standardize t'ai-chi ch'üan for wushu tournaments, because many tai chi teachers had either moved out of China or stopped pedagogy after the Chinese Civil War. They wanted to create a routine that would be much less difficult to learn than the classical 88 to 108 posture solo manus forms.

Another 1950s form is the "97 movements combined t'ai-chi ch'üan form", which blends Yang, Wu, Lord's day, Chen, and Fu styles.

In 1976, they developed a slightly longer demonstration form that would not require the traditional forms' retentiveness, residuum, and coordination. This became the "Combined 48 Forms" that were created by iii wushu coaches, headed past Men Hui Feng. The combined forms simplified and combined classical forms from the original Chen, Yang, Wu, and Sun styles. Other competitive forms were designed to exist completed inside a six-minute time limit.

In the late 1980s, CSC standardized more competition forms for the four major styles too equally combined forms. These five sets of forms were created past different teams, and later approved by a committee of wushu coaches in China. These forms were named afterward their style: the "Chen-fashion national competition form" is the "56 Forms". The combined forms are "The 42-Form" or simply the "Competition Form".

In the 11th Asian Games of 1990, wushu was included as an detail for competition for the first time with the 42-Form representing t'ai-chi ch'üan. The International Wushu Federation (IWUF) applied for wushu to be office of the Olympic games.[20]

Taijiquan was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2020 for Mainland china.[21]

Styles [edit]

The v major styles of tai chi are named for the Chinese families who originated them:

- Chen style ( 陳氏 ) of Chen Wangting (1580–1660)

- Yang style ( 楊氏 ) of Yang Luchan (1799–1872)

- Wu Hao style ( 武氏 ) of Wu Yuxiang (1812–1880)

- Wu style ( 吳氏 ) of Wu Quanyou (1834–1902) and his son Wu Jianquan (1870–1942)

- Sun style ( 孫氏 ) of Sunday Lutang (1861–1932)

The well-nigh pop is Yang, followed by Wu, Chen, Dominicus and Wu/Hao.[9] The styles share underlying theory, but their training differs.

Dozens of new styles, hybrid styles, and offshoots followed, although the family unit schools are accepted as standard by the international customs. Other of import styles are Zhaobao tàijíquán, a shut cousin of Chen style, which is recognized by Western practitioners; Fu style, created by Fu Chen Sung, which evolved from Chen, Sun and Yang styles, and incorporates movements from Baguazhang (Pa Kua Chang)[ citation needed ]; and Cheng Human being-ch'ing style which simplifies Yang fashion.

Nigh existing styles came from Chen mode, which had been passed downward every bit a family hole-and-corner for generations. The Chen family chronicles record Chen Wangting, of the family'southward 9th generation, as the inventor of what is known today as tai chi. Yang Luchan became the first person exterior the family unit to learn tai chi. His success in fighting earned him the nickname Yang Wudi, which ways "Abnormally Large", and his fame and efforts in teaching greatly contributed to the subsequent spreading of tai chi noesis. [ citation needed ] The designation internal or neijia martial arts is also used to broadly distinguish what are known every bit external or waijia styles based on Shaolinquan styles, although that distinction may be disputed by mod schools. In this broad sense, all styles of t'ai chi, likewise every bit related arts such every bit Baguazhang and Xingyiquan, are, therefore, considered to be "soft" or "internal" martial arts.

U.s. [edit]

Choy Hok Pang, a disciple of Yang Chengfu, was the first known proponent of tai chi to openly teach in the Us, beginning in 1939. His son and pupil Choy Kam Human emigrated to San Francisco from Hong Kong in 1949 to teach t'ai-chi ch'üan in Chinatown. Choy Kam Man taught until he died in 1994.[22] [23]

Sophia Delza, a professional person dancer and student of Ma Yueliang, performed the kickoff known public demonstration of tai chi in the U.s. at the New York City Museum of Mod Art in 1954. She wrote the showtime English linguistic communication book on t'ai-chi, "T'ai-chi ch'üan: Trunk and Mind in Harmony", in 1961. She taught regular classes at Carnegie Hall, the Actors Studio, and the United Nations.[24] [25]

Zheng Manqing/Cheng Man-ch'ing, who opened his schoolhouse Shr Jung t'ai-chi after he moved to New York from Taiwan in 1964. Unlike the older generation of practitioners, Zheng was cultured and educated in American means,[ clarification needed ] and thus was able to transcribe Yang's dictation into a written manuscript that became the de facto manual for Yang style. Zheng felt Yang's traditional 108-move form was unnecessarily long and repetitive, which makes information technology hard to learn.[ citation needed ] He thus created a shortened 37-move version that he taught in his schools. Zheng's class became the dominant form in the eastern U.s. until other teachers immigrated in larger numbers in the 1990s. He taught until his death in 1975.[26]

United Kingdom [edit]

Norwegian Pytt Geddes was the first European to teach tai chi in Britain, property classes at The Place in London in the early 1960s. She had start encountered tai chi in Shanghai in 1948, and studied with Choy Hok Pang and his son Choy Kam Human being (who both also taught in the The states) while living in Hong Kong in the late 1950s.[27]

Lineage [edit]

Annotation:

- This lineage tree is not comprehensive, just depicts those considered the "gate-keepers" and most recognised individuals in each generation of the respective styles.

- Although many styles were passed down to respective descendants of the same family, the lineage focused on is that of the martial art and its main styles, not necessarily that of the families.

- Each (coloured) style depicted below has a lineage tree on its corresponding article page that is focused on that specific manner, showing a greater insight into the highly meaning individuals in its lineage.

- Names denoted by an asterisk are legendary or semi-legendary figures in the lineage; while their involvement in the lineage is accustomed by most of the major schools, it is not independently verifiable from known historical records.

Modern forms [edit]

The Cheng Homo-ch'ing (Zheng Manqing) and Chinese Sports Commission brusque forms are derived from Yang family forms, but neither is recognized as Yang family tai chi past standard-bearing Yang family teachers. The Chen, Yang, and Wu families promote their own shortened sit-in forms for competitive purposes.

| ( 杨澄甫 ) Yang Chengfu 1883–1936 tertiary gen. Yang Yang Big Frame | |||||||||||||

| ( 郑曼青 ) Zheng Manqing 1902–1975 4th gen. Yang Curt (37) Class | Chinese Sports Commission 1956 Beijing (24) Form | ||||||||||||

| 1989 42 Competition Class (Wushu competition form combined from Chen, Yang, Wu & Sun styles) | |||||||||||||

Purposes [edit]

The primary purposes of tai chi are wellness, sport/self-defense and aesthetics.

Practitioners mostly interested in tai chi's health benefits diverged from those who emphasize self-defense, and as well those who attracted by its aesthetic appeal (wushu).

More traditional practitioners hold that the 2 aspects of health and martial arts make up the fine art's yin and yang. The "family unit" schools present their teachings in a martial art context, whatever the intention of their students.[28]

Health [edit]

Tai chi's health training concentrates on relieving stress on the body and heed.

In the 21st century, tai chi classes that purely emphasize health are popular in hospitals, clinics, customs centers and senior centers. Tai chi's low-stress grooming method for seniors has become better known.[29]

Sport/self-defence [edit]

As a martial fine art, tai chi emphasizes defense over assail and replies to difficult with soft. The ability to use tai chi as a form of combat is the test of a student's understanding of the art. This is typically demonstrated via contest with others.

Practitioners test their skills against students from other schools and martial arts styles in tuishou ("pushing hands") and sanshou competition.

Aesthetics [edit]

Wushu is primarily for show. Forms taught for wushu are designed to earn points in competition and are more often than not unconcerned with either wellness or self-defense force.

Philosophy [edit]

The philosophy of Taiji is to go along Yin and Yang in flux. When 2 forces push each other with equal strength, neither side moves. Motility cannot occur until 1 side yields. Therefore, a key principle in tai chi is to avoid using strength direct against strength (hardness against hardness). Lao Tzŭ provided the archetype for this in the Tao Te Ching when he wrote, "The soft and the pliable will defeat the hard and strong."

Conversely, when in possession of leverage, one may desire to apply hardness to force the opponent to get soft. Traditionally, tai chi uses both soft and hard. Yin is said to be the mother of Yang, using soft power to create hard power.

Traditional schools also emphasize that one is expected to show wude ("martial virtue/heroism"), to protect the caught, and testify mercy to i'south opponents.[4]

Forms [edit]

Training involves two principal features: taolu (solo "forms"), a sequence of movements that emphasize a directly spine, abdominal animate and a natural range of motion; and tuishou ("pushing hands") for grooming with a partner and in a more than practical manner. Traditionally, Taijiquan also has Dan Shi (Unmarried Form Practice) which practice a specific motility from Taolu.

Solo (taolu, neigong and qigong) [edit]

Taolu (solo "forms") is a choreography that serves every bit the encyclopedia of a martial art. Tai chi is often characterized by dull movements in Taolu practice, and ane of the reasons is to develop trunk awareness. Accurate, repeated exercise of the solo routine is said to retrain posture, encourage circulation throughout students' bodies, maintain flexibility, and familiarize students with the martial sequences unsaid by the forms. The traditional styles of tai chi have forms that differ in aesthetics, merely share many similarities that reverberate their mutual origin.

Solo forms (empty-mitt and weapon) are catalogues of movements that are practised individually in pushing easily and martial awarding scenarios to prepare students for self-defense training. In most traditional schools, variations of the solo forms can be practised: fast / slow, small-circle / big-circle, square / circular (different expressions of leverage through the joints), low-sitting/high-sitting (the caste to which weight-bearing knees stay bent throughout the course).

Breathing exercises; neigong (internal skill) or, more than commonly, qigong (life free energy cultivation) are practiced to develop qi (life free energy) in coordination with physical movement and zhan zhuang (standing like a post) or combinations of the 2. These were formerly taught equally a separate, complementary grooming system. In the terminal threescore years they accept get meliorate known to the full general public.

Qigong versus tai chi [edit]

Qigong involves coordinated motion, breath, and awareness used for health, meditation, and martial arts. While many scholars and practitioners consider tai chi to be a blazon of qigong,[30] [31] the ii are usually seen as separate but closely related practices. Qigong plays an important role in grooming for tai chi. Many tai chi movements are part of qigong practice. The focus of qigong is typically more on health or meditation than martial applications. Internally the main difference is the menstruation of qi. In qigong, the flow of qi is held at a gate point for a moment to aid the opening and cleansing of the channels.[ clarification needed ] In tai chi, the flow of qi is continuous, thus allowing the development of power by the practitioner.

Partnered (tuishou and sanshou) [edit]

2 students receive instruction in tuishou ("pushing hands"), one of the cadre training exercises of t'ai-chi ch'üan.

Tai chi's martial aspect relies on sensitivity to the opponent's movements and center of gravity, which dictate appropriate responses. Disrupting the opponent'southward center of gravity upon contact is the primary goal of the martial t'ai-chi ch'üan student.[thirteen] The sensitivity needed to capture the center is caused over thousands of hours of showtime yin (irksome, repetitive, meditative, low-impact) and then afterwards calculation yang (realistic, agile, fast, high-impact) martial grooming through taolu (forms), tuishou (pushing hands), and sanshou (sparring). Tai chi trains in three basic ranges: close, medium and long. Pushes and open up-manus strikes are more common than punches, and kicks are usually to the legs and lower torso, never higher than the hip, depending on style. The fingers, fists, palms, sides of the hands, wrists, forearms, elbows, shoulders, back, hips, knees, and feet are commonly used to strike. Targets are the optics, throat, eye, groin, and other acupressure points. Chin na, which are joint traps, locks, and breaks are as well used. Most tai chi teachers wait their students to thoroughly learn defensive or neutralizing skills first, and a student must demonstrate proficiency with them before learning offensive skills.

Martial schools focus on how the energy of a strike affects the opponent. A palm strike that looks to have the aforementioned movement may be performed in such a way that it has a completely different effect on the opponent'southward torso. A palm strike that could simply push button the opponent backward, or instead be focused in such a way as to elevator the opponent vertically off the footing, changing heart of gravity; or that it could projection the force of the strike into the opponent'southward trunk with the intent of causing internal damage.

Most development aspects are meant to be covered within the partnered practice of tuishou, and so, sanshou (sparring) is non commonly used as a method of training, although more avant-garde students sometimes practise by sanshou. Sanshou is more common to tournaments such as wushu tournaments.

Weapons [edit]

Variations of tai chi (taiji) involving weapons also exist. Weapons training and fencing applications use:

- the jian, a straight double-edged sword, practiced as taijijian;

- the dao, a heavier curved saber, sometimes chosen a broadsword;

- the tieshan, a folding fan, also called shan and proficient as taijishan;

- the gun, a 2 chiliad long wooden staff and practiced as taijigun;

- the qiang, a ii grand long spear or a 4 one thousand long lance.

More exotic weapons include:

- the large dadao and podao sabres;

- the ji, or halberd;

- the cane;

- the sheng biao, or rope dart;

- the sanjiegun, or three exclusive staff;

- the feng huo lun, or wind and fire wheels;

- the lasso;

- the whip, concatenation whip and steel whip.

Attire and ranking [edit]

Primary Yang Jun in sit-in attire that has come to be identified with tai chi

In practice traditionally no specific uniform is part of tai chi. Mod 24-hour interval practitioners commonly vesture comfortable, loose T-shirts and trousers fabricated from breathable natural fabrics, that let for free movement. Despite this, t'ai-chi ch'üan has become synonymous with "t'ai-chi uniforms" or "kung fu uniforms" that normally consist of loose-fitting traditional Chinese styled trousers and a long or brusque-sleeved shirt, with a Standard mandarin collar and buttoned with Chinese frog buttons. The long-sleeved variants are referred to every bit Northern-mode uniforms, whilst the short-sleeved, are Southern-style uniforms.

The clothing may exist all white, all black, black and white, or whatsoever other colour, more often than not a unmarried solid colour or a combination of ii colours: i colour for the garment and another for the binding. They are usually made from natural fabrics such equally cotton or silk. They are usually worn by masters and professional person practitioners during demonstrations, tournaments and other public exhibitions.

Tai chi has no standardized ranking arrangement, except the Chinese Wushu Duan wei exam system run by the Chinese wushu clan in Beijing. Nearly schools do not use belt rankings. Some schools present students with belts depicting rank, similar to dans in Japanese martial arts. A simple uniform element of respect and allegiance to ane'southward instructor and their methods and community, belts also mark hierarchy, skill, and achievement. During wushu tournaments, masters and grandmasters often wear "kung fu uniforms" which tend to have no belts. Wearing a belt signifying rank in such a state of affairs would exist unusual.

Seated tai chi [edit]

Seated tai chi sit-in

Traditional tai chi was adult for cocky-defense, but it has evolved to include a graceful course of seated exercise now used for stress reduction and other health conditions. Often described as meditation in motion, seated tai chi promotes serenity through gentle, flowing movements. Seated tai chi exercises is touted by the medical community and researchers. It is based primarily on the Yang short class, and has been adopted by the general public, medical practitioners, tai chi instructors, and the elderly. Seated forms are not a simple redesign of the yang short grade. Instead, the practice attempts to preserve the integrity of the form, with its inherent logic and purpose. The synchronization of the upper body with the steps and the animate adult over hundreds of years, and guided the transition to seated positions. Marked improvements in balance, blood force per unit area levels, flexibility and musculus strength, peak oxygen intake, and body fat percentages can be achieved.[32]

Health [edit]

A Chinese woman performs Yang-style tàijíquán.

Clinical studies exploring tai chi's effect on specific diseases and wellness weather exist, though there are not sufficient studies with consequent approaches to generate a comprehensive decision.[33]

Tai chi has been promoted for treating various ailments, and is supported by the National Parkinson Foundation and Diabetes Commonwealth of australia, among others. However, medical bear witness of effectiveness is lacking and enquiry has been undertaken to address this.[34] [35] A 2017 systematic review institute that it decreased the falls in older people.[36]

A 2011 comprehensive overview of systematic reviews of tai chi recommended tai chi to older people for its physical and psychological benefits. No conclusive evidence showed benefit for any of the other weather researched, including Parkinson's disease, diabetes, cancer and arthritis.[34]

A 2015 systematic review found that tai chi could be performed by those with chronic medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, center failure, and osteoarthritis without negative effects, and found favorable furnishings on functional exercise capacity .[37]

In 2015 the Australian Government's Department of Health published the results of a review of alternative therapies that sought to identify any that were suitable for coverage by health insurance. T'ai-chi was ane of 17 therapies evaluated. The study concluded that depression-quality evidence suggests that tai chi may have some beneficial wellness effects when compared to command in a express number of populations for a limited number of outcomes.[35]

See also [edit]

- Martial arts

- Self-healing

- Wushu

References [edit]

- ^ Defoort, Carine (2001). "Is There Such a Thing equally Chinese Philosophy Arguments of an Implicit Fence". Philosophy East and W. 51 (3): 404. doi:x.1353/pew.2001.0039. S2CID 54844585.

Just equally Shadowboxing (taijiquan) is having success in the West

- ^ "Wudang Martial Arts". Prc Daily. 2010-06-17.

Wudang boxing includes boxing varieties such as Taiji (shadowboxing)

(...) - ^ Bai, Shuping (2009). Taiji Quan (Shadow Boxing), Bilingual English-Chinese. Beijing University Press. ISBN9787301053911.

- ^ a b Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN978-0-7914-2654-8. [ page needed ]

- ^ Morris, Kelly (1999). "T'ai Chi gently reduces blood pressure in elderly". The Lancet. 353 (9156): 904. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75012-1. S2CID 54366341.

- ^ Cheng Man-ch'ing (1993). Cheng-Tzu's Thirteen Treatises on T'ai Chi Ch'uan. North Atlantic Books. p. 21. ISBN978-0-938190-45-5.

- ^ Sun Lu Tang (2000). Xing Yi Quan Xue. Unique Publications. p. three. ISBN0-86568-185-6.

- ^ Ranne, Nabil. "Internal power in Taijiquan". CTND. Retrieved 2011-01-01 .

- ^ a b c d Wile, Douglas (2007). "Taijiquan and Taoism from Religion to Martial Fine art and Martial Fine art to Religion". Journal of Asian Martial Arts. Via Media Publishing. xvi (iv). ISSN 1057-8358.

- ^ Lam, Dr. Paul. "What should I wear to practise Tai Chi?". Tai Chi for Health Plant. Retrieved 2014-12-29 .

- ^ Fu, Zhongwen (2006). Mastering Yang Mode Taijiquan. Louis Swaim. Berkeley, California: Blue Snake Books. ISBNone-58394-152-5. [ page needed ]

- ^ Wong Kiew Kit (1996). The Complete Volume of Tai Chi Chuan: A Comprehensive Guide to the Principles. Element Books Ltd. ISBN978-1-85230-792-9.

- ^ a b Wu, Kung-tsao (2006). Wu Family unit T'ai Chi Ch'uan ( 吳家太極拳 ). Chien-ch'uan T'ai-chi Ch'uan Association. ISBN0-9780499-0-X. [ page needed ]

- ^ 由《輔行訣臟腑用藥法要》到香港當代新經學. ASIN B082B24CNP.

- ^ "International Wushu Federation". iwuf.org. Archived from the original on 2006-02-09.

- ^ a b Henning, Stanley (1994). "Ignorance, Fable and Taijiquan". Journal of the Chen Fashion Taijiquan Enquiry Association of Hawaii. 2 (3). Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2009-11-23 .

- ^ "Origins and Evolution of Taijiquan". Chinafrominside.com . Retrieved 2016-08-20 .

- ^ "Taijiquan – Brief Analysis of Chen Family Boxing Manuals". Chinafrominside.com . Retrieved 2016-08-xx .

- ^ "Thirteen Postures of Taijiquan". egreenway.com . Retrieved 2019-09-16 .

- ^ "Wushu likely to be a "especially-set" sport at Olympics". Chinese Olympic Committee. October 17, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-13 .

- ^ "Taijiquan". UNESCO Civilisation Sector. Retrieved 2021-03-06 .

- ^ Choy, Kam Man (1985). Tai Chi Chuan. San Francisco, California: Memorial Edition 1994. [ ISBN missing ]

- ^ Logan, Logan (1970). Ting: The Caldron, Chinese Art and Identity in San Francisco. San Francisco, California: Glide City. [ ISBN missing ]

- ^ Dunning, Jennifer (July 7, 1996), "Sophia Delza Glassgold, 92, Dancer and Teacher", The New York Times

- ^ Inventory of the Sophia Delza Papers, 1908–1996 (PDF), Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, February 2006

- ^ Wolfe Lowenthal (1991). There Are No Secrets: Professor Cheng Man Ch'ing and His Tai Chi Chuan. N Atlantic Books. ISBN978-one-55643-112-8.

- ^ "Pytt Geddes (obituary)". The Telegraph. 21 March 2006. Archived from the original on iv Dec 2007. Retrieved xvi Jan 2020.

- ^ Woolidge, Doug (June 1997). "T'AI CHI". The International Mag of T'ai Chi Ch'uan. Wayfarer Publications. 21 (3). ISSN 0730-1049.

- ^ Yip, Y. 50. (Autumn 2002). "Pivot – Qi". The Journal of Traditional Eastern Health and Fitness. Insight Graphics Publishers. 12 (three). ISSN 1056-4004.

- ^ Yang, Jwing-Ming (1998). The Essence of Taiji Qigong, Second Edition : The Internal Foundation of Taijiquan (Martial Arts-Qigong). YMAA Publication Center. ISBN978-ane-886969-63-6.

- ^ YeYoung, Bing. "Introduction to Taichi and Qigong". YeYoung Culture Studies: Sacramento, CA <http://sactaichi.com>. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2012-01-xvi .

- ^ Quarta, Cynthia W. (2001). Tai Chi in a Chair (get-go ed.). Fair Winds Press. ISBN1-931412-60-X.

- ^ Yang GY, Wang LQ, Ren J, Zhang Y, Li ML, Zhu YT, Luo J, Cheng YJ, Li WY, Wayne PM, Liu JP (2015). "Evidence base of clinical studies on Tai Chi: a bibliometric analysis". PLOS One. 10 (iii): e0120655. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1020655Y. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0120655. PMC4361587. PMID 25775125.

- ^ a b Lee, Chiliad. S.; Ernst, Eastward. (2011). "Systematic reviews of t'ai chi: An overview". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 46 (ten): 713–8. doi:x.1136/bjsm.2010.080622. PMID 21586406. S2CID 206878632.

- ^ a b Baggoley C (2015). "Review of the Australian Government Rebate on Natural Therapies for Individual Wellness Insurance" (PDF). Australian Government – Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 Dec 2015.

- Lay summary in: Scott Gavura (November 19, 2015). "Australian review finds no do good to 17 natural therapies". Science-Based Medicine.

- ^ Lomas-Vega, R; Obrero-Gaitán, E; Molina-Ortega, FJ; Del-Pino-Casado, R (September 2017). "Tai Chi for Hazard of Falls. A Meta-analysis". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 65 (9): 2037–2043. doi:10.1111/jgs.15008. PMID 28736853. S2CID 21131912.

- ^ Chen, Yi-Wen; Hunt, Michael A.; Campbell, Kristin L.; Peill, Kortni; Reid, W. Darlene (2015-09-17). "The effect of Tai Chi on four chronic weather – cancer, osteoarthritis, middle failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary illness: a systematic review and meta-analyses". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50 (7): bjsports-2014-094388. doi:ten.1136/bjsports-2014-094388. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 26383108.

Farther reading [edit]

Books [edit]

- Gaffney, David; Sim, Davidine Siaw-Voon (2014). The Essence of Taijiquan. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN978-1-5006-0923-8.

- Bluestein, Jonathan (2014). Research of Martial Arts. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN978-1-4991-2251-0.

- Yang, Yang; Grubisich, Scott A. (2008). Taijiquan: The Fine art of Nurturing, The Science of Ability (second ed.). Zhenwu Publication. ISBN978-0-9740990-i-ix.

- Frantzis, Bruce (2007). The Power of Internal Martial Arts and Chi: Combat and Energy Secrets of Ba Gua, Tai Chi and Hsing-I. Bluish Snake Books. ISBN978-i-58394-190-4.

- Davis, Barbara (2004). Taijiquan Classics: An Annotated Translation. North Atlantic Books. ISBN978-1-55643-431-0.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1986). A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Subconscious Symbols in Chinese Life and Idea . Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN0-415-00228-1.

- Choy, Kam Man (1985). Tai Chi Chuan. San Francisco, California: Memorial Edition 1994. [ ISBN missing ]

- Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Hugger-mugger Transmissions. Sweetness Ch'i Press. ISBN978-0-912059-01-3.

- Bail, Joey (1999). See Human being Spring Encounter God Autumn: Tai Chi Vs. Engineering science. International Promotions Promotion Pub. ISBN978-ane-57901-001-0.

Magazines [edit]

- Taijiquan Journal ISSN 1528-6290

- T'ai Chi Magazine ISSN 0730-1049 Wayfarer Publications. Bimonthly.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tai_chi